War is a victorious, perhaps bitter, maybe a painful playground for adults. In war, we imagine soldiers moving to shoot their enemies, nurses rushing to heal the injured, politicians and generals posing in front of battle plans, and civilians running away from the crossfire. Our memories of war are ingrained with images of adults trying to make sense out of that chaos. For years we have been surrounded by timeless photographs and movies about that war that to this day, we envision the war strongly as an adult’s world.

But what about the children? Where is the child’s place in our social memory of the Pacific war?

Finding the child’s place in social memory entails an understanding of social memory and the value of children’s experiences in relation to the grand historical World War II narrative. Their frail voices in World War II histories speak of how much their war experiences have been neglected. However, as these children find their voices as adults, the recollection of their World War II experience as children becomes unbearably loud.

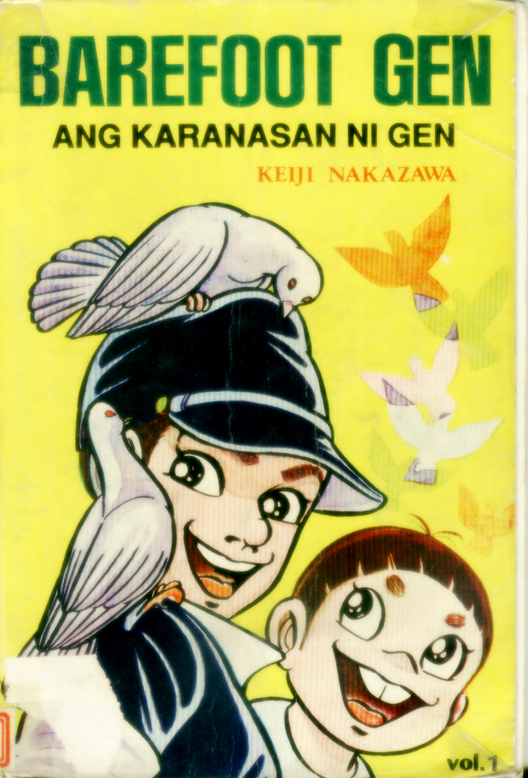

These are the memories of three Japanese children during the war against the images of Japanese childhood as constructed by Japan’s propaganda machinery. The memories of Keiji Nakazawa, Osamu Tezuka, and Shigeru Mizuki present a different story of the Pacific War —providing a fresh yet powerful social memory that makes us question on how war affects people at all ages.

The Junior Citizens of the strong Japanese Nation

At the onset of the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Japan has been at war for more than 40 years. War was a reality among Japanese children and the government took advantage of this situation by shaping these children’s mind towards war. They were making Junior Citizens out of the Japanese children.

At the onset of the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Japan has been at war for more than 40 years. War was a reality among Japanese children and the government took advantage of this situation by shaping these children’s mind towards war. They were making Junior Citizens out of the Japanese children.

Education was at the heart of the mobilization of children for war. As early as the Meiji period, morals education were taught to all children. By the early 1930s, the government used radio broadcasts that were played in schools to stir sentiments of the children.

When War Minister Sadao Araki retired in 1936, he decided to divert his attention to school as he revamped the system when he was appointed as the minister of education. As Araki was at the heart of the “Imperial Way†ideology, he pushed his nationalist sentiments unto education as well. He noted that in order to “mobilize the spirit of the nation,†there was a need for “self-reflection and self-discipline.†[1]

By 1937, new ethics textbooks were introduced in schools by Education Ministry: Kokutai no Hongi (The True Meaning of our National Structure) and Shinmin no Michi (The Way of the People). Over 2 million copies of Kokutai no Hongi were distributed in schools and became central in the moral and spiritual mobilization of children in wartime Japan. Shinmin no Michi was closer to general textbook: a mix between the bible and the Kokutai no Hongi.

These textbooks stirred nationalist sentiments, emphasizing on the greatness and uniqueness of Japan.[2] Values of patriotism, loyalty, and respect for the kokutai (nation) were imbedded unto the minds of children so that they would not fall for individualism and materialism. Because the family is the lifeblood of the nation, it is important that each individual must think in context of their families in as much as they must take into consideration their larger family: the nation.[3] To draw children’s attention towards the study of the books, they even employed cartoonists to illustrate their books in order to inspire children to support their efforts.[4] It was of utmost importance that Japan does not commit the same mistakes of the Taisho era.

Once Hideki Tojo became the prime minister of Japan in 1941, Araki went ahead and made changes in the structure of the public school system. The aim of education was to create Junior Citizens out of children. Ideally, these children should comprehend the nationalist values of the empire. More than that, they should have the skills that will allow them to fully contribute to the nation. As Junior Citizens, these children should have the capacity, small as they are, to contribute to the war effort. Hence, Araki pulled all the strings in making every child work for the nation.

Most children began studying through primary education. However, they were also required to attend National Youth Schools (Kokumin Seinen Gakko). In these youth schools, nationalism was stressed greatly as children were immersed in propaganda and nationalists texts. Children were encouraged to offer themselves to the state should emergency arise and that they should “guard and maintain the prosperity†of the Imperial Throne.[5] Many students graduate from these youth schools at the age of 13.

Once these children reached middle schools, they were offered advanced training in helping the military or training with them. In schools, children learned patriotic calligraphy that was either displayed for their homes or in public. Composition classes were dedicated to themes of patriotism. Hands-on experiments with crops and livestock were incorporated in science and math courses in order to boost production.

After middle school, children were either enrolled in vocational schools or at specialized high schools. In earlier years, there were various military training camps that boys could participate in. Either way, these children were given military training or other skills. In the 159th issue of Photographic Weekly Report on 12 March 1941, they showcased photos of children performing various tasks. In its accompanying article named “Youth are the Advance Army Shouldering Responsibility for Japan,†girls were seen taking cooking and housekeeping classes. While boys were seen doing military drills, horticulture, fishing, and operating heavy machinery. According to David Earhart, author of Certain Victory: Images of World War II in Japanese Media, many of these young men would eventually be drafted before the end of the war.[6]

Things changed as soon as the war reached its last stretch. Children were taken out of schools and boys, still as young as middle school were directly sent to training camps while girls were in factories producing war materials. Younger children were either working in the fields or in ammunition factories.[7]

There was no time for universities for most children at that time. With the recruitment age as young as 20, many boys were sent straight to the army before they even had the choice to go to college. At one point, even boys as young as 15 were encouraged to “volunteer†in the army. If they chose not to go, they would be sent immediately to training centers or labor camps where they were either malnourished or exhausted.[8]

By 1944, these children not only became junior citizens but junior warriors as well. School children were separated from their parents and were bunked in schools and temples where teachers would assign them tasks and duties to support the war effort. This ranged from agricultural jobs to intense military training like tank drivers or even kamikaze pilots.[9] Towards the final stages of the war, various articles of young boys taking part in the “Special Attack Forces†were published in hopes to publicize the suicide missions of these young soldiers.[10] These last sacrifices were a mark of the complete spiritual mobilization of the Japanese youth. All of them willingly gave their lives for their country, whether they died under fire in the middle of the battlefield or under exhaustion in the middle of a rice field.

Outside schools, children also played a part in lifting the spirits of the soldiers and were often used in Japanese War propaganda. Children were effective tools in encouraging soldiers to bravely continue the war. They made various contributions, both formally and informally, in the war effort.

The most informal method in using children in propaganda was through letters, care packages, and drawings sent to fathers and other relatives who were already sent off shore to fight for the Japanese cause. Girls were asked to sew good luck charms and other military paraphernalia that symbolizes the undying love and support of families to their soldier relatives. At times, they would even ask children to sing songs for encouragement and these performances were broadcasted on the radio.

The government also used children as images of self-sacrifice hoping that they would serve as an inspiration not only to other children but to adults as well. Even the youngest of children were not spared from participating in war. In place of war bonds, children were encouraged to buy mame saiken (bean-sized bonds) in hopes that their contributions can encourage older people to invest in war bonds.

Outside of the government, various civil groups united children to help the war effort. There was mock East Asian Children’s Council that “aimed to promote Asian unity under the direction of ‘older brother’ in Japan.†There were also Youth Work Corps, Youth Agricultural Volunteers, and Youth Air Corps who were trained in order to be part of the war machinery. These groups were often publicized in order to encourage war sympathies.[1]

As such, the children were seen as happy and eager contributors to the war effort as they wore a brave smile during those difficult times. It was as if the Junior Citizens had no problem with the war.