In a dinner where Japan’s most elite gathered to discuss Tozai News’ plan for the Ultimate Menu, most men proclaimed that the most luxurious cuisine, there the most ultimate menu in the world is French. Each man was not short of giving their compliment on French ingredients and cuisine however one man couldn’t handle this pretext for the Ultimate Menu.

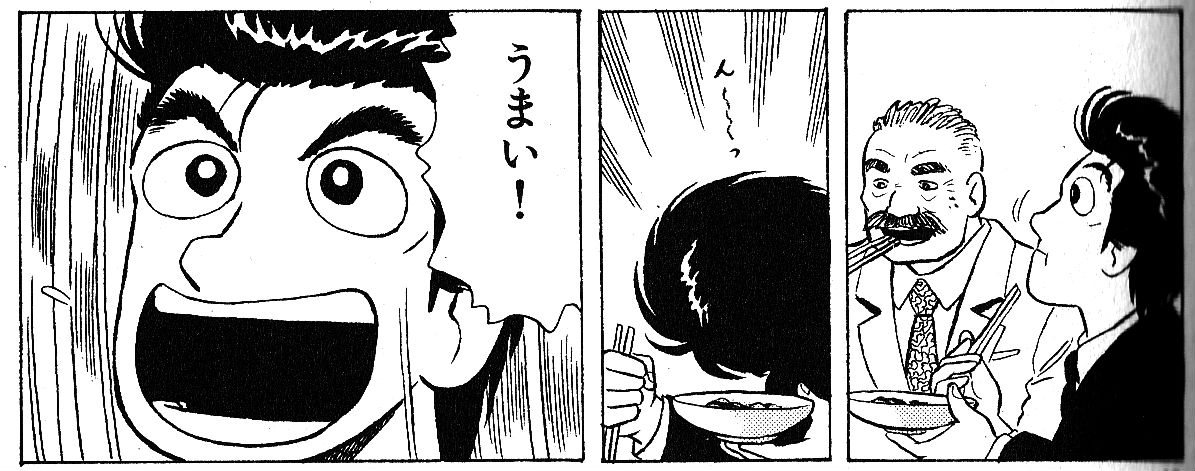

Yamaoka Shiro, Tozai News’ Ultimate Menu journalist called them and said Japanese Cuisine and this pretentiousness was all a . He asked the man to give him a week to find the ingredient that was just as luxurious as a French foie gras. Many in the room were not having any of it, but a week later, Yamaoka gives them a plate that almost fooled everyone. What they had thought was French foie gras was in fact the liver of a monkfish, ankimo.

Stories of East vs. West often line up in the pages of Oishinbo. If you consider the time that Japan has been open to the West, this whole East-West foodie tension should have been done and over with by the time Oishinbo was written. But does the fact that the comic continues to question the superiority of Western cuisine make Oishinbo a post-colonial text? Is the comic a tale of Japan’s own battles in preserving their own food culture?

The Exotic Japanese Cuisine of Oishinbo

I really didn’t think so much about this until I started to read the English editions of Oishinbo. The 8 volumes published by Viz are fantastic collections of Oishinbo’s best and I won’t deny that they were entertaining. I just happened to notice that these editions mostly tackled Japanese cuisine.

I remember seeing similar ala carte editions in Japanese and while they too tackled Japanese cuisine, there were also compilations for steak, Chinese, Italian, and Indian cuisine. These compilations were in the same breath as the US ala carte as they too contained Tetsu Kariya’s essays about food. A part of me wondered if Viz would ever feature these other editions but upon hearing from friends, this dream is probably lost in licensing.

See, in reading the Viz editions, I had an overwhelming appreciation for Japanese cuisine and tradition, to a degree that now I feel that the set has exoticized Japan. Just like the foreigners featured in the chapters, I was blown away by Japanese cuisine. When you have an American chef going all the way to Japan just to learn the art of sushi and the expat wooing his fellow expat with some skewers, I too was moved by Japanese gastronomy enough to host this feast for Oishinbo. In many ways, I too sought for the refinement of Japanese etiquette and it didn’t take long for me to realize how much I’ve stained my chopsticks.

I felt like Japan was at the top of the culinary world with Oishinbo and Yamaoka leading the way. Somehow, in my amazement, I failed to notice the little things that weren’t exactly all Japanese. The Japanese sushi chef serving those fancy Californian maki. The sake industry that compromised sake brewing for profit. If Oishinbo was supposed to capture the essence of Japanese cuisine, it too also captured the ‘bastardization’ of its food culture.

Japan as the West

‘Bastardization’ might be a harsh word, but what English readers haven’t read are the hundred of stories in Oishinbo that questions Japan’s forgetfulness when it comes to their cuisine just because they want to impress someone or get ahead in the global business game. I’m not saying that this is particularly a Western trait or that I’m rationalizing that it was all the fault of the west. What I’m saying is that in reading the comic, this degradation of food cultures (both Japanese and Non-Japanese) is a response to the westernization and much further the globalization of Japan. Oishinbo couldn’t have been written at a better time because it captured the spirit of this period in Japan that longed to be at par, if not equal or superior to the West.

Japan’s economy was at its peak when Oishinbo started in 1983. The salaryman was the new samurai and they changed Japan through economics. More than just conquering local economies, the largest of these companies wanted to conquer the world. So imagine how many of traveled and brought ideas and flavors from the globe without really fully knowing the heart of these ideas as they translate in Japanese. From here comes the countless stories not shown in the American edition.

Yamaoka would feature countless of times how a particular chef was in trouble with Kaibara Yuzan because he didn’t get things right. For example, a Japanese Italian chef had trouble in making his carbonara and Yamaoka showed him how to properly do it. Yamaoka challenged a Chinese chef who, despite being popular, couldn’t get his barbecued pork (char siew) right. My favorites often involve flashy businessmen who show off their knowledge of foreign cuisine only to be shot down by Yamaoka.

Yes. We get it. Japan can do things better than you.

If anything, these kinds of chapters reflect Japan’s own longing to position themselves in the same footing the West. And not only are the Japanese doing these, but because of Japan’s own “Western arrogance”, foreigners too are trying to find themselves in Japan. People compromise the heart of their own cuisine only to bring the people what they think they want. The broken nature of the English editions breaks Oishinbo’s connection with Japanese society at that time and fails to show the growth of the Japanese palate and gastronomy.

At most we can see that this generation of gourmands have made it difficult for foreign cuisines to position themselves in Japan’s changing society. But more than foreign cultures losing a bit of their own culture for Japanese people, even Japan is losing a bit of themselves in their food. With people wanting to eat foreign food and with foreign food wanting to cater to Japan’s tastes, Japanese food seems as lost as sake was to that young actor. This social and cultural tension is something we see Yamaoka and Kurita continue to deal with. Does he marry the two cultures or does he let them have their own way? How far can they let them have their own way without compromising the other?

Sustaining and Innovating Japan’s Food Culture

As the series progresses, Yamaoka would often find himself at the edge of this cultural tension. On one end he feels strongly about Japanese flavors but at the same time he learns new ideas from his trips abroad and he wishes to preserve other people’s cuisines. He realized that there’s a world of flavors out there that Japan should enjoy but these flavors could be costly to Japan’s almost forgotten cuisine. As his father educates his still naive and idealist tongue, Yamaoka would often choose the most difficult road: never compromise. Keep what is Japan Japan’s and the others to their own. Offer the truest flavors to people and let their tongues decide what tastes best.

This decision created various dishes both memorable to many fans. In talking with a Japanese friend, she and I would often fondly look at some of the earlier dishes that aren’t necessarily Japanese but were particularly heartwarming. For example, there was a feature on “soul food” which featured American gumbo and Greek salad. Then we start looking back at the little things like how they used a CT-scan to understand the importance of packing rice for sushi or how the best of tempura chefs had to listen carefully to the oil to know when tempura is cooked for the picking. These food need not be Japanese. As long as it’s a meal that can touch one’s soul, it is as great as any other food.

At the very least, stories on local fare revolved around the appreciation of local ingredients, Japan’s need to have a sustainable agriculture, and the legacy of Japan’s own culinary techniques. That said, the series fails to highlight the price involved in sustainable food. They too have trivialized the domestic economics and ecological and environmental sustainability of local Japanese cuisine, citing only the challenged Japanese food experience without contextualizing it in Japanese society. Those ankimo and mentaiko don’t come cheap in Japan. With flavors that demands authenticity in a country that has a limited amount of agrarian resources, most of the ingredients in Oishinbo demand a steep price. Of course, Oishinbo is not the kind of cooking that considers its economics, as they would include matsutake mushrooms more in their rice than spring onions. If Oishinbo says anything, these ingredients don’t come easy. And the easies that you can have them is getting a Japanese mom to cook it for you. Remember those soft yet packed onigiri in Joy of Rice?

Foreign cuisine also doesn’t come as easy as they often experience these abroad or in fine French restaurants. As much as it appears sustainable, it is also not economical. It is fast food fare for the high class salaryman which might just be very apt for the audience of this globalized manga but not to all Japanese. If anything, this makes Oishinbo look like the food manga for everyone’s gourmand dreams.

But it does have its benefits. Tempura is perhaps one of the best foreign adaptations in Japanese cuisine. So is that yuba gratin. And that miso beef marinade and beef garlic donburi. I could go on and on with the countless dishes featured in this comic that has adapted foreign flavors, techniques, and ingredients to Japanese cuisine. Perhaps I can proudly say that outside of bastardized culinary movements in Japan, there are innovations like this that reminds us Japan perhaps has become cosmopolitan.

Japanese cuisine as a struggling globalized cuisine

Perhaps Tetsu Kariya’s residence in Sydney has given him a different perspective of how Japan looks at food. I used to think that if Japan had questions so early about sustainable cuisine and organic produce before the West even raised it, then perhaps they might be ahead of this whole food revolution game. But that’s not true, actually. I think for many of us who have been living in urban cities, we’ve been divorced from the idea that our food comes from somewhere. And Oishinbo is one of the few who remembers where our food comes from. And this isn’t just a Japanese culinary philosophy but already a global culinary practice.

An expertise on ingredients and techniques can transform the most foreign meals into something Japanese. Katsu curry can’t be found in India. Nor is tartar sauce in France any similar to those served as sides beside Ebi fry. Only the best elements are placed together to create an entirely brand new set of dishes. And it’s quite telling how a once insular country managed to create new flavors pulled from their own experienced and made it their own.

I’m afraid the English edition has failed to highlight is this globalized characteristic of Japanese cuisine. Apart from delicate kaiseki or shojin ryori, hamburgs, steaks, and fried chicken is just as much a part of their cuisine as well. While they have all been placed under the guise of Chinese or Western or Local fare, at the end of the day, ramen (which is considered Chinese cuisine in Japan) is a dish that is completely Japanese.

I’m quite sure that some Japanese cuisine purists might be turning in their graves with this abomination but like the new developments in the sake industry, this “bastardization” can also be viewed as an innovation, a new phase in Japanese cuisine. There’s a reason why chefs, from Bourdain to Ripert, have an ongoing love affair with Japan and its cuisine. It isn’t so much about the exoticized/weird/unusual Japanese meals but with their exposure to various aspects of Japan’s culinary culture, they realized that its gastronomy continues to change in response to the changes in Japanese society.

That’s the best legacy Oishinbo has given to Japan’s food culture and manga. And until we see these unpublished dimensions of Japanese cuisine, Oishinbo will simply be that comic about Japanese food.